Reflecting on a summer with the Cayuga Lake Watershed Network

Written on February 1st , 2021 by Abbey Yatsko

(ADAPTED VERSION FROM a crumb)

I know many readers of a crumb will find the view of Cayuga Lake, overlooking Cornell’s west campus from Libe Slope, to be all too familiar. Cayuga Lake is one of the hallmark treasures of Ithaca, and a gold-tinted summertime sunset reflecting over Cayuga’s waters is unmatched, and more or less quintessential to the Cornell experience. Normally, the blustery winters of Ithaca catapult me back to these memories of warmer days, but recently my memories were called upon when I received a particular handbook in the mail.

The handbook, titled ‘Lakeside Living in a Changing Climate’, is a publication that I modestly claim as one of my own collaborations. This past summer, I was afforded the unique opportunity to work alongside the Cayuga Lake Watershed Network (CLWN) to create a guide to lake-friendly and climate-aware living practices for lakeside homeowners. The Cayuga Lake Watershed Network, as expressed in their mission statement, “identifies key threats to Cayuga Lake and its watershed and advocates for solutions that support a healthy environment and vibrant, sustainable communities”. In working through this handbook project, I found every bit of the mission statement to come true through my work. Even though it is now the dead of winter and this is clearly not the timeliest review of my experience with CLWN, I figure it is still worth sharing impactful takeaways from the experience, nonetheless.

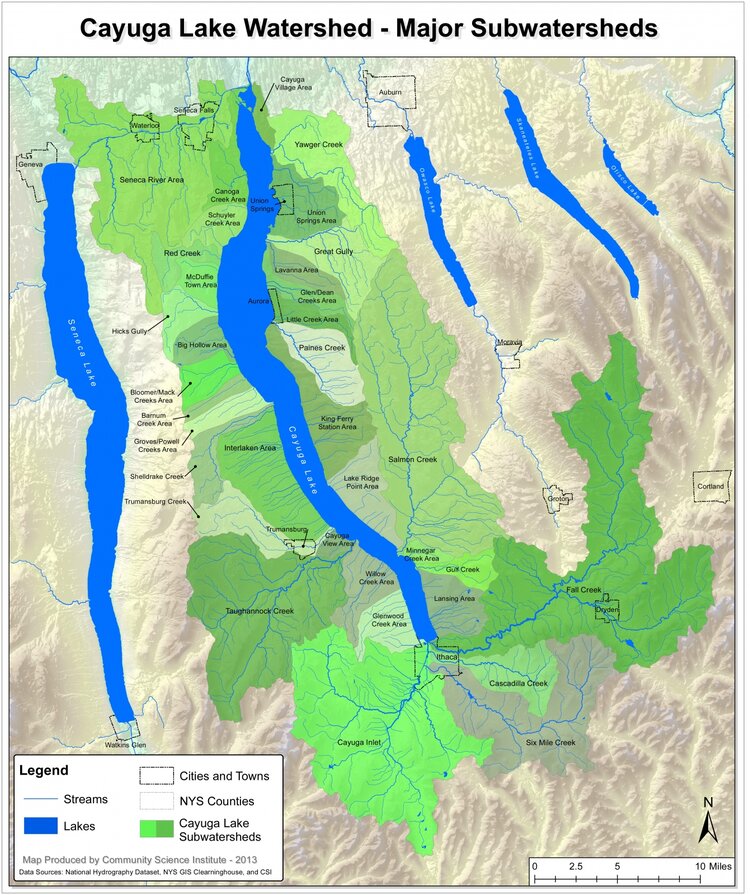

Map of the Cayuga Lake Watershed

Map of the Cayuga Lake Watershed

So why does the CLWN exist? Well, there is a similar story that follows many human-inhabited places: they start off as abundant in their resources and well-being, and then human intervention and activity alters the ecology, health, and prosperity of the land, oftentimes in a negative way. In the Cayuga Lake region, lakeside development has disturbed key shoreline habitat by welcoming higher rates of erosion, and surrounding land use change (such as clearing forests for agriculture and development) has funneled excess nitrogen and phosphorus into the lake basin. Ultimately, human intervention in the region has changed the way water moves throughout the watershed. While the aforementioned perturbances represent only a handful of examples, the CLWN actively addresses topics of this flavor in order to protect the lake. Without proper protection and management (this word makes me wince a little, I’ll get to that in a bit) of human activities and pursuits within the areas surrounding Cayuga Lake, many of the services of the lake or activities that we cherish in will degrade through time. A tourist economy based on the health and appearance of Cayuga will go bust if harmful algal blooms (HABs) run rampant each summer. Generally speaking, if the community as a whole fails to think in a climate-forward way, the dooms of global climate change will catch up and eventually begin to show their true colors in our little pocket of the world. So, the CLWN steps in to monitor changes in the lake and watershed ecosystem though time and also acts to make the community aware when potential harm is on the horizon.

Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs) in Cayuga Lake

Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs) in Cayuga Lake

Back to the handbook project: in my time with the CLWN, I worked alongside John Abel to investigate and compile resources to promote sustainable habits and best environmental practices for lakeside living. The project goal was to take this information, condense it into an attractive, readable form, and then distribute the resource to lakeshore residents. In the process of writing the handbook, I engaged with numerous perspectives on grassroots-led environmental stewardship as well as local experts in fields such as home energy efficiency and wastewater treatment. From citizen science research on harmful algal blooms taking on an ecological perspective to taking a look at local land ordinances and building codes to infuse a governmental perspective, it was further proved to me that no environmental stewardship goal can be accomplished without an interdisciplinary mindset.

The handbook itself provides encourages practices within three main categories: reducing carbon emissions, lake-friendly living, and community engagement. We take a dive into numerous topics, spanning from home energy efficiency to shoreline protection to personal vehicle emissions. To be honest, the handbook covers an almost overwhelming wealth of information, yet the goal is not to have an individual take each action step that we suggest (although if we were all to embrace every last word of the handbook, that would really mobilize some change!). Rather, I see the handbook as more of a ‘choose your own adventure’ kind of deal, governed by personal financial constraints, individual time commitments, and the reality that some things are out of our individual control. I feel like this is an overarching theme of a crumb as well: every one of us will have a separate sustainability ‘journey’ tailored to the logistics of our individual lives. Some of you may have read my recent brushing up on toothcare article, and may have not been too compelled to give toothpaste tabs a go – rather, you were more inspired to shop local, so you gave that a try and it stuck with you. Each route to more sustainable living will take a different form, just as the Lakeside Living handbook looks give options as to where homeowners have the potential to make a difference.

Organizations such as the CLWN are so critical in communicating this message of sustainable living. All of the CLWN staff that I met through this project were perfect examples of community members that simply want the best for their human and ecological communities. I was lucky enough to spend some socially distant time with John Abel (Project Director and CLWN Board Member), Hilary Lambert (Watershed / Executive Director), and Jennifer Tufano (Program Associate), each possessing a strong connection to the lake and an even stronger sense of dedication toward their work. John was kind enough to show me the Cayuga shoreline from the perspective of his boat, pointing out new developments and clear-cut plots as we cruised northward on a sunny July morning. Over the course of decades living on the west side of the lake, John notices these changes within the context of time and the health of the lake. From Hilary, I took away a passion for her work and a fiery, can-do attitude when it comes to addressing outdated practices and conventions that put the environment on the back-burner. Hilary, a long-time Cayuga Lake resident as well, has watched the ecosystem grow and change through time. She has personal accounts of how things were, way back when, and what they are changing into, oftentimes at the expense of the lake. These are the people that we should be listening to and learning from when it comes to monitoring our ecosystems and organizing collective action for their betterment. Recognizing environmental harms must be followed by a change in our actions, for the better interest of us all, but more importantly the lake itself.

I mentioned before that I do not quite agree with the term ‘management’ when it comes to a discussion of our natural resources and landscapes. However, this term dominates our vernacular and some titles in our government system. When you think about it, nature has been managing itself with high levels of perfection for millennia, and will certainly continue to do so with or without humans as the millennia draw on. If anything, ‘people-management’ is more necessary than ‘environmental management’ will ever be! This differentiation was part of my vision for the handbook, and I hope that readers find it to stimulate such self-reflections of where people-management can step in to favor the lake. There are many behavioral changes that we can take up that will help to prevent nutrient runoff (lay off on the excessive chemical garden fertilizer), aquatic invasive arrivals (wash off boats when transporting between bodies of water), and wastewater treatment mistakes (regular septic system servicing). After all, our sustainability journey is marked by our actions, not our management ideas or eventual plans.

In summary, working with the CLWN made me fall in love with the message that our work continually spread: when your community cares about their natural resources, it simply makes sense to take action and revise the conventional practices that brought about harm. The lake, in some poetic way, is a lifeline, something we all share in common, whether we depend on its waters for fishing, recreation, or something as quaint and simple as a sunset from Libe Slope.

If you have any interest to page through the handbook, you can find it here. It is my pride and joy to have produced the content and designed the handbook alongside John, so call this shameless self-promotion if you must! Also, don’t hesitate to check out the CLWN website to learn more about the organization’s message and initiative in the Cayuga Lake community. I can attest to the fact that it is quite a fine group of lovely, sustainable-minded humans. Thank you so much for taking the time to read our messages!

abbey

cover photo credit to Bill Hecht